Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

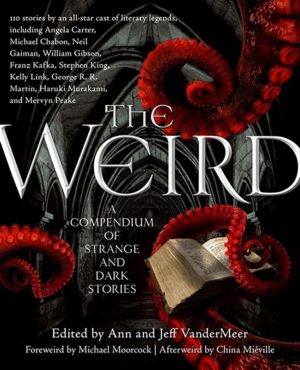

This week, we cover Olympe Bhêly-Quénum’s “A Child in the Bush of Ghosts,” first published in 1949 in Liaison d’un été. You can find it in English in Ann and Jeff Vandermeer’s The Weird, translator not credited (possibly Bhêly-Quénum himself?).

Spoilers ahead!

“I felt that the bush was not supposed to be the abode of the dead but of the living. Wasn’t I one of them?”

Codjo is eleven years old when his uncle Akpoto takes him on a visit to his farm. They follow the district council road to a “path of fine golden sand which meandered through a high and dense forest.” They ford a small river and continue along the sandy path. The deeper they venture into the forest, the more uneasy Codjo becomes, and eventually “the humidity pervaded [his] whole body, and the sense of fear became intolerable.” To counter it, he pesters Akpoto with questions.

They reach a clearing, but the sky is so obscured by the forest canopy that Akpoto can’t read time by the sun. He gives Codjo fruit and tells him to wait—he’ll return shortly. Codjo suppresses the urge to cry; there’s “nothing [he] detests so much as giving unbridled expression to our sorrows.” After eating his orange and guavas, he feels he has “certainly waited more than [he] shall ever be able to wait again” and, oppressed by the “frightening calm” of the bush, he starts walking without thought to direction. He encounters a big woman who’s concealed, face to feet, in a white lappa. His heart pounds and he wants to shout, yet he runs to the woman as a baby to his mother. She passes “in mute indifference,” then uncovers her head to reveal a “fleshless skull.” Codjo flees. Without running, the woman remains a constant distance behind him.

He bursts out of the forest at the railroad tracks and meets Akpoto, who’s already finished his business. He says the bush isn’t dangerous, but acknowledges Codjo’s fright at being left behind. He doesn’t believe Codjo got to him without crossing the river until they trace the game trail flattened by his panicked flight—it returns riverless to the clearing. Akpoto’s dumbfounded to miss a river which he’s always assumed had its source in the forest.

Buy the Book

Echo

It will turn out that Codjo’s game-track is actually the quickest shortcut to Akpoto’s farm.

Codjo wants to prove the skeletal figure was a hallucination. He also wants to surprise Akpoto by himself discovering the source of the river. He’s always been a spoiled child, kept from school because his parents thought him sickly. Tired of feeling coddled and useless, he seizes an unwatched moment to escape back into the bush.

He follows his game-track to the clearing and ventures into the pathless underbrush. There he spots a chameleon that takes on the indigo of his neckcloth. Codjo’s reminded of his great-grandfather who praised the chameleon’s ability to always find its destination, adjust to its surroundings, and never look back. He decides he’ll emulate the lizard, but without forgetting he’s a human being, “the only creature who would not be forgiven voluntary subservience.”

In another clearing, “sealed off… in tragic solitude,” Codjo again meets the white-wrapped skeleton. He neither runs nor approaches, preserving his dignity; after all, he is a man, while it is “nothingness in motion.” The skeleton offers its hand. He clasps its bony fingers and lets it lead him forward.

The skeleton reminds him both of his great-grandfather and of his grandmother. When they died, eight-year-old Codjo sat vigil over their remains and even tried to keep his parents from putting his grandmother into her coffin. He supposes he’s holding his grandmother’s hand now, but concludes that the skeleton could have been male or female in life. It doesn’t matter.

The skeleton brings him safely through thorns and wild animals to an underground tunnel adorned with symbolic graffiti. It slopes down to a crypt occupied by seventy-seven skeletons. They sit up at the guide’s bow. Codjo feels each represents someone he’s known. He’s glad to see them, but he remembers his quest for the river’s source and boldly interrogates the skeletons.

They remain silent. His guide disappears. Codjo presses on through the tunnel. A “majestic skeleton” holding a skull-topped shinbone lets him pass, lightly stroking his head with the skull. Farther on, Codjo falls abruptly asleep. A voice murmurs “Wassaï” in his ear, and indeed he has entered that “disturbing, exciting paradise.” Five paths diverge through flowering hedges, and beyond those lies a vast field of kola-nuts dwarfed by giant trees in which night birds sing. White smoke rises from the hidden fires of sorcerers, but Codjo finds a “little house of joy without a keeper.” Within are “ravishing young beauties” whose “nimble legs… readily intertwining, [push him] gently into voluptuous depths.” After this initiation, he knows he’s been in Wassaï, “fearsome black flower slowly unfolding in the deep nights of a dwelling without a master.”

He wakes on a mountainside from which a spring gushes. He descends as if “gently impelled” by a protecting hand, following the spring to a natural canal. Though he’s disappointed he didn’t find the source of the river, he does find the river itself, flowing parallel to the railway line!

The tracks lead him home, where he’s stunned to find a funeral in progress. At his entry, some mourners flee, while others seem paralyzed by fear. Codjo was missing for three days, and the diviners confirmed he was dead!

Codjo explains he has only been on a walk, from which he comes back “body and soul, cured from the fear of death.” His parents are incredulous, but in exchange for his promise never to disappear again, they agree to demand no further explanation.

“Everything was all right again.” Still, Codjo wonders: “How long did this dream last?” He concludes: “I shall never know.”

What’s Cyclopean: The night birds in Wassaï produce “lugubrious shrieks.”

Weirdbuilding: “Bush” manages to get surprisingly weird while drawing on archetypes from the Hero’s Journey and underworld descents.

Anne’s Commentary

Where on earth or in its adjacent dreamlands is this “disturbing, exciting paradise” called Wassaï? If Randolph Carter ever visited it, he omitted any mention of the place from his otherwise comprehensive somno-travelogues. This is unfortunate, if not surprising, as Carter was notoriously reticent about his spicier adventures. Rumor has it that Miskatonic University’s most closely guarded occult archives may house pertinent material. Try getting past the guardians of those collections, however. Our indomitable Carl Kolchak has been trying to “informally” access them for years and has the scars to prove it.

Offer him a fine single-malt Scotch whiskey, and he’ll show them to you.

My own search for “Wassaï” turned up no pertinent entries. If any reader knows its nature and whereabouts, please let Carl know. He promises he won’t divulge the information to minors, and he’ll foot the bar bill. Although, according to today’s story, minors are welcome in Wassaï. Eleven-year-olds, even.

At least such highly precocious ones as Bhêly-Quénum’s Codjo.

Codjo tells us his father has kept him home because he’s “sickly and unable to stand the hustle and bustle of a school in session.” Sickly? I wouldn’t describe a kid who can walk thirteen kilometers in the hot sun plus more in the forest as constitutionally unfit. Dad, an elementary school teacher, may be more concerned about that “hustle and bustle,” having noticed a particular sensitivity about his son. Given Codjo’s experiences both times he goes into the bush, maybe Dad’s concern is warranted; in which case, how should we read it that Codjo can see skeletal ghosts? That he can, like King’s Mrs. Todd, exploit impossible shortcuts? That he can pass between spheres of existence? Call the spheres what you will: lands of the living and the dead, realms of waking and dream, worlds of the mundane and of the fantastic. To put it at its most basic, either Codjo’s deluded or he’s gifted.

I guess “deluded” could cover everything from over-imaginative to psychotic. “Gifted” could mean he’s a great storyteller or he’s a psychic. Or, hell, the weirdness in the bush could have been a dream, with the presumably adult Codjo asking at the end “How long did this dream last?” What was real, what wasn’t? His grown-up answer may be the only honest one: “I shall never know.”

Young Codjo isn’t so tolerant of uncertainty. He doesn’t accept Akpoto’s assertion that he must have re-forded the river. Having reasoned away the possibility he saw a ghost, he must prove it mere hallucination by another trip into the bush. While he’s in the bush anyway, he might as well trace the river to its source—and he’s so determined to get the answer that he brashly demands it of a full council of skeletal ancestors.

Curiously, when Codjo and his skeletal guide first enter the tunnel leading to the crypt, he hears “the gentle, distant murmur of a stream.” When he cries “in a tragic voice” for the skeletons to tell him the river’s source, he again hears “murmurings of the water, then a groan followed by the sound of a torrent rushing away.” Could it be that he’s found the wellspring of the river in the haven of the dead? Are they themselves its spiritual fountainhead?

After leaving the crypt, Codjo decides against retracing the underground path he followed with the skeleton; he trusts that by looking forward rather than back, he will, like the chameleon, always find his destination. I guess the council of ancestors saw enough in Codjo to deem him worthy of initiation into one aspect of manhood. He encounters another skeleton in the tunnel, one as majestic as a king and carrying a bony scepter to boot. Scepters, the emblem of royal power, are pretty blatantly phallic. With the skull-end of his, this skeleton strokes Codjo’s head. Thus authorized, Codjo passes into waxing light and the smell of fields and then a state he describes as “a long sleep.” Wassaï is his dream, or his sojourn in a dreamland of lush vegetation. If there’s a difference between the two.

Bhêly-Quénum places intriguing emphasis on the freedom the inhabitants of Wassaï enjoy. Sorcerers throw orgies beneath the trees and devour souls unimpeded. The “young beauties” live in “a little house of joy without a keeper,” a “dwelling without a master.” So there are no procurers here, no madams, no pimps, no coercion, instead an unbridled carnality Codjo’s waking world would label “rebellious sex.”

Codjo’s waking from Wassaï is a “coming from another world” not to the expected bush but to a mountainside. From the summit, Codjo discovers “the immensity of space above the earth,” a new concept for him. A spring flows down the mountain to a natural canal and hence to the forest river; if not the ultimate source of the river, it’s a tributary step toward wisdom.

The wisdom he imparts at his premature funeral is precocious enough, though he delivers it casually. Nobody’s dead, death doesn’t exist, no dead man returns. Perhaps further evidence that Codjo’s parents know he’s irremediably special: His mother sums up Codjo’s non-explanations with the murmur, “Oh, this child!”

Oh, this child indeed.

So, has anybody found directions to Wassaï yet? Oh for a Dreamlands Map app!

Ruthanna’s Commentary

In some ways, a child’s perspective is the perfect way to portray weirdness. We all come into the world, after all, utterly bewildered by the nature of reality. What’s more cosmically strange than having to learn the nature of gravity? (Please, please, stop dropping everything off the high chair. I swear the food is never going to hover.) At the same time, they may be perfectly blasé about things that an adult reader—now taking the laws of physics for granted—finds deeply disturbing. Add to that the tension of watching a kid face whatever-it-is, and/or the uncanniness of an apparently innocent child revealing themselves as something else, and it can make for a potent mix.

It can also be a challenging one. Machen and Atherton, in my opinion, flub their attempts. Bixby, perhaps sensibly, goes light on giving us Anthony’s direct point of view, and does so brilliantly—but Anthony isn’t exactly your average child.

Strictly speaking, “Bush of Ghosts” isn’t narrated by a child, but by an adult looking back on a formative experience. On the other hand, I kind of suspect that experience is death, and thus future-Codjo isn’t exactly an adult. The depiction is effective, at any rate, shifting between disturbing events and disturbing reactions to those events. The Vandermeers’ introduction describes it as a ghost story that’s also a “surreal vision.” Perhaps what it does is shift between the two like some face/vase optical illusion, levels of reality never resolving into definitive answers.

For this uncertainty, a child’s already open-ended reality is a useful starting point. And the narration starts as you might expect: simple, straightforward, grounded in immediate sensation and absolute emotional reactions. I love the moment where humidity and fear are made one, the clamminess of terror thoroughly embodied in not only Codjo but his environment.

But that’s almost the last moment of clear embodiment that we get. Future-Codjo almost immediately rejects his emotions—“there is nothing I detest so much as giving unbridled expression to our sorrows”—even while sympathetically describing child-Codjo’s unbridled sorrow at losing his grandparents. In the bush he loses physical agency, marching like an automaton. He can’t scream, but wishes he could to provide “the illusion that I still was myself, a human being.” Future-Codjo, apparently, knows or believes that he isn’t any such thing. And hasn’t felt fear since.

These dissociations continue throughout, sensation and action and body and emotion all happening or failing to happen with independent dream logic. Sometimes he insists on his personhood, sometimes he feels like “a wretched carcass.” He dismisses his guide and follows it eagerly, calls it nothing and calls it human in the same breath. Thorns don’t tear skin, lions sniff and wander off indifferently. Really, the skeletal psychopomp is the least of the strangeness. Even the subsequent psychedelic orgy barely makes the top five.

Despite his humanity now being an illusion, or perhaps because of it, Codjo has strong opinions about what it means to be human. You can’t “be forgiven voluntary subservience,” which suggests his involuntary losses of control as excuse or justification.

At some point, this all slips into a more familiar form: the rite-of-passage journey to the underworld, seeking “the source of the river” through an underground tunnel that is totally not symbolic of the birth passage that is also the pathway to death. Oh, wait, no, it totally is that thing. You can tell from the symbols painted on the wall, sex and death and probably Sigmund Freud’s signature somewhere off in the corner. (Freud’s theories, a clinical psychologist once told me, are great for literary analysis.)

And then he returns home, and instead of being hailed as a hero or shaman, the diviners have all declared him dead. He hasn’t eaten or slept for three days and he feels fine. And everything is all right again—and either his bush experiences or that all-rightness is a “dream” whose length he still doesn’t know.

All in all, maybe it’s a good thing for his equanimity that he doesn’t believe in death. And for ours that he assures us the dead don’t return.

Next week, join us for Chapter 3 of Hilary Mantel’s Beyond Black.

Ruthanna Emrys’s A Half-Built Garden is now out! She is also the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic, multi-species household outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

Olympe Bhêly-Quénum and Amos Tutuola are both Nigerians, more or less contemporaries, and both wrote about the Bush of Ghosts – sort of an hallucinatory otherland.

There are a couple of interesting things here. One is the common misconception that chameleons change color based on their surroundings- the author surely would have seen chameleons in the wild and known that’s not how they do. So is the chameleon a portent?

The other is… Well. Codjo is eleven, and participates in an orgy. There’s a persistent myth that the age of consent in Nigeria is 11. It isn’t, it’s 18, but I wonder if 11 is the cultural age of consent if not the legal age.

Before I lived in China, I would read Chinese stories and think, “why did this happen? why did she say it that way? why is that object mentioned?” The stories seemed improvised, lacking intention. Then after living there for years, I could finally understand some of the little choices authors make. X imagery points to Y symbolism, which everyone in the culture recognizes because of Z historical event. That sort of thing. I wonder if that’s why I often feel adrift reading Nigerian stories.

@1, Olympe is actually from Benin, to the west of Nigeria. I’d imagine there is at least some cultural affinity, but I do not know enough about the history of the two nations to say for certain.

@3 True, my mistake, thanks for pointing it out. However, he appears to have spent at least part of his early life in Nigeria.

I wonder if he and Tutuola were of the same ethnicity and could draw upon the same cultural reservoir. Colonial boundaries often divide otherwise coherent groups in that part of the world.

Anyway I thought that it was interesting that both authors use the same term for a phantasmogoric wilderness where the protagonist has strange adventures.

I never found the psychoanalytic style of criticism very useful, or even appealing. It seems to reveal more about the obsessions of the psychoanalysts than what any author actually had in mind. I too ran afoul of some prime potty-minds when young, but as a budding ace [among other things] my loyalties lay elsewhere. Especially after finding that the early exponents of that school had some pernicious ideas about certain sectors of the populace being inherently, eternally defective.

Rivers and springs are interesting enough in their own right that they hardly need metaphoring into something else. Seems there was a passel of Conrad fans that decided any journey upstream was a voyage into prehistory and chaos, but that can get just as tiresome for some, and just as useless after a while, as seeing everything through the lens of (some people’s idea of) sex. Good for a laugh I guess, but any interpretation of what someone else wrote should be considered conjectural and provisional, unless the author makes a statement about what they really had in mind.

Enjoy it if it’s what you like, but don’t anyone take it too seriously. That said, I still would like to see you take on “A Bit of the Dark World”, by Fritz Leiber, “The Door to Saturn”, by Clark Ashton Smith, “Black Thirst” by C.L. Moore, “The Great White Space” by Basil Copper, “Worms of the Eartth” by Robert E. Howard, “The Striding Place” by Gertrude Atherton, “Magna Mater” by Arinn Dembo, and the Weird of Hali heptology by J.Michael Greer. I hope you will get to these sometime in the months and years to come.

And I know you don’t like Machen, but if you ever feel masochistic enough to do “The Great God Pan”, be sure and follow it with the sequel, “Helen’s Story” by Roseanne Rabinowitz, from Aqueduct Press.

As it happens, I’m working my way through the VanderMeers’ Weird collection, huge as it is – though I haven’t yet reached this particular story. I liked your reference to King’s ‘Mrs Todd’, a story which really resonated with me.

The name Codjo in this story rang a bell, partly because of the similarity to the name of a certain rabid St. Bernard*, but mostly because I’d recently been reading about the 2018 rediscovery of the slave ship Clotilda, and of Cudjoe Lewis (born Oluale Kossola), one of the last survivors** of the Atlantic slave trade in the United States who was brought on that ship to Alabama from Dahomey (now Benin). From Wikipedia:

So, @1 and @3, there is indeed a Nigeria/Benin (and Ghana) connection via the Gbe language family, so maybe that explains why both Tutuola and Bhêly-Quénum wrote about the Bush of Ghosts.

*Cujo the dog was named after the supposed alias*** of Willie Wolfe, one of Patty Hearst’s kidnappers.

**Specifically Lewis/Kossola was the third-to-last known survivor of the Atlantic slave trade, and he died in 1935, only two years after my dad was born. The last known survivor, Matilda McCrear, died in 1940, a year before my mom was born. The past is frighteningly close sometimes.

***Wolfe actually called himself Kahjoh, so ultimately this part has nothing to do with anything.

According to this site, the story’s English translator is Willfried Feuser, and here (second footnote at the bottom) it’s giving the original publication in French as 1968, not 1949, and the publication date of Feuser’s translation as 1981. (It really bothers me when translators aren’t credited. Credit the translators, book people! If they do a good job, I want to seek out more of their translations, and if not, I want to know to avoid anything in future with their name under the author’s!)

Way Too Many More Things @@@@@ 8: Thank you! I tried to track that down and couldn’t.

@7 Way Too Many Things – Thanks for doing that digging around. I had taken a brief look at language family dispositions in West Africa but didn’t go as deep as you did.

Interesting to know. Tutuola’s novels fascinated me.